Essays by Robert Fuller

Writings About Writing: Opening Thoughts, by Robert Fuller

Before I begin, it must be said that I have not been active on Medium.com for nearly a year. Suffice it to say that my attention was occupied with other things, mostly, a suite of three visual design apps that I’ve been developing for the Android. (Stay tuned for more on that, once my next article is ready for posting on Medium...)

The last article I posted on Medium (4/18/2022) was “Deus-Ghost in the Ex-Machina”, which is the seventh of 64 poems in my newly-published poetry collection Etymologicon :

http://books.google.com/books/about?id=dXapEAAAQBAJ

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=dXapEAAAQBAJ

On April 1, 2022, I published an essay discussing in detail the origins of my poetry collection Etymologicon from the initial set of 16 poems that I wrote, which became every fourth poem in the set, starting with the fourth one, “Quarry”. I refer you to that article if you wish to “dig” (pun intended) further—or venture down the “delf trail.”

My approach to writing is inextricably linked, in part, to my 50+ years of background and experience in the arena of classical music, mainly piano and composition.

All aspects of life necessarily involve some degree of repetition; we can easily see that in the rhythms of daily life. There is also evolution, or change, and it is in the balance of these two basic forces, along with an inevitable revolution, in the sense of return—or the feeling of return—that life and its creative energies demonstrate themselves.

This same balance of forces pertains as well to our individual and collective creative efforts as human beings. If these forces are out of balance in either direction, to any great extreme, those creative efforts, in my assessment, become to some degree or other less potent.

I can be a rather unforgiving critic of pop culture, and this is so because it is my opinion that the balance of forces of which I speak, as it pertains to pop culture, is largely out of balance in the direction of excessive repetition.

We’re all aware, certainly, of the “echo chambers” that so mark—and often befoul, pollute, and degrade—our digital world nowadays. Anyone’s vile, malicious, evil thoughts can be sent into that echo chamber, that social media amplifier, and emerge out the other end as the next trending click-bait meme thingy, the next viral plague infecting the gullible and uninformed.

But alas, I digress...

However, I have more to say about repetition (and amplification by repetition), namely, that we as a society tend to be drawn to individuals and groups who are already well-known, famous, or even infamous. This is another form of repetition, in the sense of reinforcement; it’s that old adage of “famous for being famous.”

In my considered assessment, the excessive adulation, even to the extent of worship, of those who have already become household names, does not really add anything of great cultural value to our human heritage; in fact, such obsession about already-famous people, quite often to the exclusion and ignoring of other creative voices, is in a way a detriment to our society.

There’s a whole other essay that could be written on a topic of this nature, but my final point in the arena of this excessive repetition and reinforcement of who (and what) is already famous, is that, in today’s world, it all comes down to this society’s errant and ill-conceived tendency to focus just about everything on one thing: Money (and the commodification, commercialization, and cooptation of just about anything that can be somehow converted into cold, hard currency, usually for the sole benefit of the already excessively-monied).

So, I am gradually working my way towards the actual topic at hand; this is kind of a random walk that eventually, miraculously, finally reaches the goal.

Very much related to the repetition/evolution dichotomy is this one: formula vs. process.

Once again, much of pop culture is based on the simple notion of taking what already sells and figuring out how to replicate, how to distill the essence of, whatever it was that made the thing that sold (or went viral), in order to ride that same bandwagon in copycat fashion, usually in order to try mimicking the commercial success of the “prototype.”

In cooking—or perhaps chemistry in general—a formula is similar to a recipe, albeit the former is by its nature much stricter, in that a recipe can usually be altered at whim without ruining the results, or causing great calamity.

And a process is related to a recipe as well, with the recipe being a kind of “middleman” between a fluid process (a relatively elastic way of proceeding when transforming something into something else) and a static, end-result formula that allows little or no possibility of variation.

At this point, going by my notes of a couple of days ago—although for good reason I’m not adhering 100% to the original order of those notes—I’m now getting more to the meat of the subtitle of this essay, “Reflections on Etymologicon.”

If the template for the above dichotomies is in the form static/fluid, then this next pair has to be expressed in this order: Narrative vs. descriptive.

Not every poem, not by any means, is essentially narrative in nature, and by its very essence, poetry tends to be imbued with descriptive qualities whether narrative in nature or not. But in the case of Etymologicon, by and large the balance is more in the direction of description. This doesn’t necessarily imply that the mode of description is completely static in nature, primarily because of the poetry’s rootedness in history via the agency of etymology.

Even when the poetry in this collection tends more toward the narrative end of the spectrum, it is not narrative in a conventional sense (if there is such a thing!); rather, it is narrative to one degree or another in the sense that—in contradistinction to the poems on the more descriptive end of the spectrum—mainly in that there is a distinct sense in which the language moves the reader in some kind of recognizable trajectory from one “place” to another.

Now, as to structure, my original line of thought along this line was that much of my approach to writing has undoubtedly been informed and influenced by my study of music, both piano and composition.

But then I considered the static/fluid dichotomy that has already surfaced in this essay, and it became obvious that the notion of (static) “structure” has its own kind of (fluid) counterpart, which might be referred to as some kind of “sandbox” or “playground”—or in mathematical set theory, a “universe”.

With regard to specifically musical notions of structure, there are all kinds of elements that could be brought up, such as sonata form, counterpoint, motivic development—and also the very underpinnings of music, such as melody, rhythm, and harmony, especially their foundations in acoustics and other aspects of physics.

However, in my experience in music composition, the progenitor to any sense of structure that results from such an act is in fact process. And this brings me back to the poem that started it all: “Quarry”—a search in the form of a dig wherein one explores the materials at hand in order to bring to the fore the nuggets contained therein.

This brings me to one of my central points, and for me, this point is the crux of my own personal “philosophy of poetry and writing”: In a word, resonance.

There are other words that I associate with how I like to work with language, but this one word really captures the essence of my philosophy.

What I mean by resonance in this context is the sense that there is a thickness, a complexity, of how the words are arranged and how they sound and signify within their context, such that they appear to “talk” to each other, often in ways that are not commonly seen or heard, in a kind of “feedback loop” that amplifies certain frequencies, colors, and so forth, much in the same way that feedback loops can occur in musical acoustics and other such phenomena in nature.

This “crosstalk” within the words of the poem, wherein the words are in some metaphorical sense “informing” each other—and making the proverbial whole greater than the sum of its parts—is to me, akin to how, in the best gustatory experiences I’ve enjoyed, each bite tends to bring out a completely different facet of the flavor profile of the food eaten.

So it’s all about richness and complexity. And at best, something new surfaces that perhaps was previously hidden.

My penultimate point in this essay is “merely” this: Poetry as polymathy, as composition, as music, as history, as philosophy...

Now, I wouldn’t by any means say that the above point is my final word on poetry, or my philosophical leanings in that arena, just as I would find it hard to imagine ever writing a poetry collection like Etymologicon ever again. Yet, there are certain ways in which my writing happens, with respect to both the preceding point and the one before that, that will persist throughout much of my writing.

Considering that the (sub-)topic of this essay concerns a poetry collection in the form of a treatise on word origins, my final word (for now) revolves around the word “poetry” itself.

In etymonline.com, my source for this word dig, the more useful entry—between “poetry” and “poem”—is the latter:

poem (n.):

1540s, “written composition in metrical form, a composition arranged in verses or measures” (replacing poesy in this sense), from French poème (14c.), from Latin poema “composition in verse, poetry,” from Greek poēma “fiction, poetical work,” literally “thing made or created,” early variant of poiēma, from poein, poiein, “to make or compose” (see poet).

From 1580s as “written composition, whether in verse or not, characterized by imaginative beauty ion thought or language.” Spelling pome, representing an ignorant pronunciation, is attested from 1856.

What stands out for me in the above are the references to “thing made or created”, and “to make or compose.”

It’s all music to my ears.

Toward a Philosophy of Poetry and Writing, by Robert Fuller

Reflections on Etymologicon

Before I begin, it must be said that I have not been active on Medium.com for nearly a year. Suffice it to say that my attention was occupied with other things, mostly, a suite of three visual design apps that I’ve been developing for the Android. (Stay tuned for more on that, once my next article is ready for posting on Medium...)

The last article I posted on Medium (4/18/2022) was “Deus-Ghost in the Ex-Machina”, which is the seventh of 64 poems in my newly-published poetry collection Etymologicon :

http://books.google.com/books/about?id=dXapEAAAQBAJ

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=dXapEAAAQBAJ

On April 1, 2022, I published an essay discussing in detail the origins of my poetry collection Etymologicon from the initial set of 16 poems that I wrote, which became every fourth poem in the set, starting with the fourth one, “Quarry”. I refer you to that article if you wish to “dig” (pun intended) further—or venture down the “delf trail.”

My approach to writing is inextricably linked, in part, to my 50+ years of background and experience in the arena of classical music, mainly piano and composition.

All aspects of life necessarily involve some degree of repetition; we can easily see that in the rhythms of daily life. There is also evolution, or change, and it is in the balance of these two basic forces, along with an inevitable revolution, in the sense of return—or the feeling of return—that life and its creative energies demonstrate themselves.

This same balance of forces pertains as well to our individual and collective creative efforts as human beings. If these forces are out of balance in either direction, to any great extreme, those creative efforts, in my assessment, become to some degree or other less potent.

I can be a rather unforgiving critic of pop culture, and this is so because it is my opinion that the balance of forces of which I speak, as it pertains to pop culture, is largely out of balance in the direction of excessive repetition.

We’re all aware, certainly, of the “echo chambers” that so mark—and often befoul, pollute, and degrade—our digital world nowadays. Anyone’s vile, malicious, evil thoughts can be sent into that echo chamber, that social media amplifier, and emerge out the other end as the next trending click-bait meme thingy, the next viral plague infecting the gullible and uninformed.

But alas, I digress...

However, I have more to say about repetition (and amplification by repetition), namely, that we as a society tend to be drawn to individuals and groups who are already well-known, famous, or even infamous. This is another form of repetition, in the sense of reinforcement; it’s that old adage of “famous for being famous.”

In my considered assessment, the excessive adulation, even to the extent of worship, of those who have already become household names, does not really add anything of great cultural value to our human heritage; in fact, such obsession about already-famous people, quite often to the exclusion and ignoring of other creative voices, is in a way a detriment to our society.

There’s a whole other essay that could be written on a topic of this nature, but my final point in the arena of this excessive repetition and reinforcement of who (and what) is already famous, is that, in today’s world, it all comes down to this society’s errant and ill-conceived tendency to focus just about everything on one thing: Money (and the commodification, commercialization, and cooptation of just about anything that can be somehow converted into cold, hard currency, usually for the sole benefit of the already excessively-monied).

So, I am gradually working my way towards the actual topic at hand; this is kind of a random walk that eventually, miraculously, finally reaches the goal.

Very much related to the repetition/evolution dichotomy is this one: formula vs. process.

Once again, much of pop culture is based on the simple notion of taking what already sells and figuring out how to replicate, how to distill the essence of, whatever it was that made the thing that sold (or went viral), in order to ride that same bandwagon in copycat fashion, usually in order to try mimicking the commercial success of the “prototype.”

In cooking—or perhaps chemistry in general—a formula is similar to a recipe, albeit the former is by its nature much stricter, in that a recipe can usually be altered at whim without ruining the results, or causing great calamity.

And a process is related to a recipe as well, with the recipe being a kind of “middleman” between a fluid process (a relatively elastic way of proceeding when transforming something into something else) and a static, end-result formula that allows little or no possibility of variation.

At this point, going by my notes of a couple of days ago—although for good reason I’m not adhering 100% to the original order of those notes—I’m now getting more to the meat of the subtitle of this essay, “Reflections on Etymologicon.”

If the template for the above dichotomies is in the form static/fluid, then this next pair has to be expressed in this order: Narrative vs. descriptive.

Not every poem, not by any means, is essentially narrative in nature, and by its very essence, poetry tends to be imbued with descriptive qualities whether narrative in nature or not. But in the case of Etymologicon, by and large the balance is more in the direction of description. This doesn’t necessarily imply that the mode of description is completely static in nature, primarily because of the poetry’s rootedness in history via the agency of etymology.

Even when the poetry in this collection tends more toward the narrative end of the spectrum, it is not narrative in a conventional sense (if there is such a thing!); rather, it is narrative to one degree or another in the sense that—in contradistinction to the poems on the more descriptive end of the spectrum—mainly in that there is a distinct sense in which the language moves the reader in some kind of recognizable trajectory from one “place” to another.

Now, as to structure, my original line of thought along this line was that much of my approach to writing has undoubtedly been informed and influenced by my study of music, both piano and composition.

But then I considered the static/fluid dichotomy that has already surfaced in this essay, and it became obvious that the notion of (static) “structure” has its own kind of (fluid) counterpart, which might be referred to as some kind of “sandbox” or “playground”—or in mathematical set theory, a “universe”.

With regard to specifically musical notions of structure, there are all kinds of elements that could be brought up, such as sonata form, counterpoint, motivic development—and also the very underpinnings of music, such as melody, rhythm, and harmony, especially their foundations in acoustics and other aspects of physics.

However, in my experience in music composition, the progenitor to any sense of structure that results from such an act is in fact process. And this brings me back to the poem that started it all: “Quarry”—a search in the form of a dig wherein one explores the materials at hand in order to bring to the fore the nuggets contained therein.

This brings me to one of my central points, and for me, this point is the crux of my own personal “philosophy of poetry and writing”: In a word, resonance.

There are other words that I associate with how I like to work with language, but this one word really captures the essence of my philosophy.

What I mean by resonance in this context is the sense that there is a thickness, a complexity, of how the words are arranged and how they sound and signify within their context, such that they appear to “talk” to each other, often in ways that are not commonly seen or heard, in a kind of “feedback loop” that amplifies certain frequencies, colors, and so forth, much in the same way that feedback loops can occur in musical acoustics and other such phenomena in nature.

This “crosstalk” within the words of the poem, wherein the words are in some metaphorical sense “informing” each other—and making the proverbial whole greater than the sum of its parts—is to me, akin to how, in the best gustatory experiences I’ve enjoyed, each bite tends to bring out a completely different facet of the flavor profile of the food eaten.

So it’s all about richness and complexity. And at best, something new surfaces that perhaps was previously hidden.

My penultimate point in this essay is “merely” this: Poetry as polymathy, as composition, as music, as history, as philosophy...

Now, I wouldn’t by any means say that the above point is my final word on poetry, or my philosophical leanings in that arena, just as I would find it hard to imagine ever writing a poetry collection like Etymologicon ever again. Yet, there are certain ways in which my writing happens, with respect to both the preceding point and the one before that, that will persist throughout much of my writing.

Considering that the (sub-)topic of this essay concerns a poetry collection in the form of a treatise on word origins, my final word (for now) revolves around the word “poetry” itself.

In etymonline.com, my source for this word dig, the more useful entry—between “poetry” and “poem”—is the latter:

poem (n.):

1540s, “written composition in metrical form, a composition arranged in verses or measures” (replacing poesy in this sense), from French poème (14c.), from Latin poema “composition in verse, poetry,” from Greek poēma “fiction, poetical work,” literally “thing made or created,” early variant of poiēma, from poein, poiein, “to make or compose” (see poet).

From 1580s as “written composition, whether in verse or not, characterized by imaginative beauty ion thought or language.” Spelling pome, representing an ignorant pronunciation, is attested from 1856.

What stands out for me in the above are the references to “thing made or created”, and “to make or compose.”

It’s all music to my ears.

(Originally published on Medium, 2/14/2023)

Four Poems From Etymologicon, by Robert Fuller

It all began with a word dripping with multiple meanings: “Quarry”. I’d already been working on a novel of that same name; I guess I must have been fascinated with the possibilities of where such a word would lead in poetry just as much as I was in the arena of storytelling.

My intent in telling you about this, in letting you in on some of my little secrets, is to let you see some of the behind-the-scenes activities that come into play when I work. You see, work is play, this is all a play; we know how it ends—or do we? Does it end?

Analysis can be dry and relatively meaningless; it can also be a key not only to understanding how someone or something works, but also a key to how you can help unlock your inspiration as you walk this Earth in relationship to your creative muse.

The four poems discussed here from my just recently published tome bearing the rather unwieldy title of Etymologicon were the first four poems that I wrote before I knew what the title was to be or what the collection would ultimately become: a treatise in word origins in poetic form.

“Quarry” was the first, and based on the way of working that I intuited even then, was the one that led to the first sixteen of these poems, all set in quatrains, four each. Each was crafted out of its predecessor via an organic process of digging deeper and asking where to go next.

The full collection, Etymologicon, is comprised of sixty-four poems; the sixteen poems that began this adventure—from “Quarry” to “The Gear Box”—have been placed in the set as every fourth poem, beginning at number four and ending at number sixty-four.

So the number four is present everywhere here in this modest poetry collection of mine. And it all began with the word that started it all: quarry. “Quarry”, you see, is at least in part based on a word origin that includes, among other things, the number four within its secrets.

Let’s start, then, with that part of the word, both as to its definitions and where they came from. You see, there are three different senses of “quarry”, and it’s the first and third of those that have “four” hidden in them—in plain sight, once you see the word origins.

When I was crafting these first four poems, my source for the definitions and word origins of “quarry” was dictionary.com; therefore, I will show you what I found there. You will find similar definitions at any of your usual online dictionary sources, but this was the one I chose at the time.

Interestingly enough, dictionary.com includes two different sets of definitions for the three different sets of meanings for this word. There are similarities, to be sure, but there may also be some subtle differences, since the first set is American English, and the second one is British.

Let’s start with the word origins, since that’s where our nugget “four” is hidden in plain sight. The American English version of these word origins seems to be more detailed and extensive, so let’s go with that. Here’s what’s listed for quarry¹:

First recorded in 1350–1400; Middle English noun quarrei, quarey, quar(r)i, from Medieval Latin quareia, quarrea, quareria, from Old French quarriere, from unrecorded Vulgar Latin quadrāria “place where stone is squared,” derivative of Latin quadrāre “to square”.

So, you see, hints of “four” are visible once you go back to Vulgar Latin and then further back to Latin. Interestingly enough, the Vulgar Latin quadrāria already points directly to places where marble and the like are mined: “place where stone is squared.” Square: a four-sided shape.

And, whereas quarry¹ is the place where square stones are mined, quarry³ denotes the square stones or tiles themselves, so the derivation is similar: First recorded in 1535–45; noun use of obsolete adjective quarry “square,” from Old French quarre, from Latin quadrātus quadrate.

I’m sure you’re aware of what the second and final set of meanings for “quarry” refers to; since it’s completely different, even though the word is the same, the derivations—and what they signify to us—are different, as well. Read this, and you’ll soon get to the heart of the matter, first recorded in 1275–1325:

Middle English quirre, querre, quirrei “parts of a deer given to the hounds,” from Old French cuiree, cuiriee, curee “viscera, entrails” (probably influenced by cuir “leather, hide, skin”), from Latin corium “skin, hide, leather”), from Late Latin corāta (plural) “entrails,” from cor “heart”.

There is a common thread, however, between all of these senses of the word “quarry”: There is a hunting for something, whether inanimate or animate, and there is also the something that is found and gathered—whether inanimate or (at some point) animate: cut stone or entrails.

In the notes I compiled in 2019, I made it clear that this first poem, “Quarry”, was in one sense a play on a kind of cycle-return (from...to...and back) aspect of existence, and its primary form was expressed in this manner: QUARRY-ESCAPE-PREY.

There is also a schematic I laid out in the first three poems: a progression from sight to sound to touch and smell, and then to taste (and tongue), and finally, to movement. This sequence also includes hidden meanings that hint at the emergence of language (hence “tongue”, or langue).

Quarries are usually, but not always, open pits from which stone, slate, marble, and the like are extracted. But before the extraction, those objects of interest or desire are typically hidden from direct view. So the primary set of opposites in my notes was this: VISIBLE-HIDDEN.

In the middle sense of the word “quarry”, if you examine its derivations, there is another way that this primary set of opposites manifests itself. Recall that these derivations involved not only “viscera, entrails” but also “skin, hide, leather”: the skin hides the viscera (as in outer-inner).

In the last two quatrains of “Quarry” there is another dichotomy introduced, that of context. My notes read thusly: outer-inner-context/earth/universe. I suppose that my line of thought was that earth was somehow “inner” and universe was “outer”—the latter “containing” the former.

I think that just about covers the main keys to my modus operandi in the writing of the poem “Quarry”. My annotations indicated that its first quatrain referred to sight, the second to sound, and the third to touch and smell. (Taste/tongue/langue came in at the last quatrain of the second poem.)

Now a few elucidations on the first poem: “What I was looking for”—this is never specified, in part because in my assessment we never really know what we’re ultimately looking for, do we?—and whatever it was, it in any case “outcloaks me”; it escapes me, literally.

So then I downplay it: “It was nothing, anyway...” We all do that, sometimes as sour grapes. But what is this “play” that happens next? When “yet somehow / It outplays me, plays away...”? What “play” is that? What does it have to do with the subject matter?

Oh, yes! The play is part of the cycle: Escape! But “away from the pollen...”? And then: “—ex cappa”? Where did these drift in? Well, we neglected to include in our word origin excavations the “escape” part of the cycle, so that’s the piece that’s missing (or hidden).

When we dig further, it turns out that ex cappa refers to the made-up word “outcloaks” and that it (ex cappa) is the derivation of “escape”: someone got “out of” the “cape or cloak”! But what about pollen!? How did that drift in? We can thank palynology (the study of pollen etc.).

What’s “cappa” mean? The thick wall on the proximal side of the corpus of a pollen grain. So it’s the outer part of what makes you sneeze. And interestingly enough, palynology as a study of particulate organic matter covers all of these: pollen counts, crime scenes, and sedimentary rocks!

That’s only the first quatrain. Then, in the first two words of the second, we see (or hear) this: “Meaning drifts...” That two-word phrase can be read in at least two ways, depending on what word you emphasize most: “meaning”, or “drifts”? So perhaps both readings are true at once.

Is “meaning” a noun? A present participle? Both? Is “drifts” a plural noun? A third person verb conjugation? Both? “Meaning drifts” reads as “signifying slow movements”, whereas the other emphasis, “Meaning drifts” reads as “what is defined floats effortlessly”.

And what is this “...from gaze to tower and back...”? Where did it come from, and where is it going (and when does it come back)? Most simply, the “gaze” was the elusive “long look” at the “thing stared at” that was nothing really, just pollen, that I was looking for but would never find.

“Tower”, though? Really!? Yes. There’s “watchtower” or “citadel” for starters, on the noun side, and if you dig into the verb side, you get not only “rise high” but also, of hawks ,“to fly high so as to swoop down on prey”—so you get sight, height, and prey all in one!

And both “gaze” and “tower” can be either noun, verb, or both. Gaze (v.): “look steadily and intently”; and tower, well, we’ve already covered that in both noun and verb forms. But with gaze and tower, who’s really looking at whom? A “gaze-hound” was a dog that followed prey by sight.

And then “...pilot-fish to osprey...”—what’s that all about? In part, old seafarers’ tales, in that a pilot fish was metaphorically thought to lead sharks to their prey, in some kind of symbiotic relationship. And osprey, a bird of prey, a sea-eagle, was also literally a “bone-breaker”.

Both forms of life, then, involving this “prey”—quarry. And the quarry-escape-prey cycle, always returning. But after this: “Meaning drifts from gaze to tower / And back, pilot-fish to osprey...” we hear something for the first time: a story told perhaps in onomatopoeia.

And in “telling / Of waves, winds, wings, and songs” we enter the realms of myth or legend, “And the swoop of the griffin...” This swoop, of the kings of beasts and birds conjoined, leads us to a strange enough place: “auspex”. An “observer of birds” or of the entrails of sacrificed animals.

But the innards are out of sight, hidden by their counterpart: quarry hiding quarry—from the earth (ground or globe, or both). You get the reference to “squared” by now; it’s the first and third forms of “quarry”. What about “squared relay”, though? Where did that come from?

Well, there’s the verb sense of “relay” and where it came from: c. 1400 (Old French), relaien, “to set a pack of (fresh) hounds after a quarry”. Note the last word. The noun form comes from this: late 14c. (also Old French), in hunting, relai, “hounds placed along a line of chase”.

So then “squared relay of pointers”—if you know that a “pointer” (and recall also the earlier reference to “gaze-hound”) is a gun dog for locating prey, usually birds—might represent a pack of hunting dogs “squared” or intent on finding whatever prey their masters were looking for.

And at the behest of their masters what was it they were looking for? Quarry, it seems, but “the place of cut stone...”!? Did those dogs take a wrong turn somewhere? Or did someone mix their metaphors? It’s “heart” to tell: it was “to locate ... the heart”—heart, at the root of quarry².

What was this “heart”, then? “The very substance of the delf trail itself.” Heart, as in “inner part of anything”—the essence, or very substance. We know the references to “trail” and “itself”. But what is this “delf” reference? It’s related to the verb “delve”, to dig: ditch, pit, quarry, mine.

So we’re still engaged in the search, and now we have hunting dogs assisting us. But will we ever find what we’re looking for? We pray, is this prey that we seek ever elusive? How will we ever find what we are looking for? Can it be found? And how do we even know what we’re looking for?

We move from Earth (globe and the ground beneath our feet) to the whole of this arising, the universe. “Parsed moment by moment by the universe...”—and this “parsed” is metaphorical, perhaps. We are possibly observed and analyzed by whatever it is we are arising within.

Or maybe it’s just a casual reference to moments passing by, mostly unnoticed, since it’s the universe “which remembers to forget in a secret place...”: time slices that have no real substance, that are just fleeting moments, that are both remembered and forgotten by whatever this all is.

And the closing lines in this last quatrain of “Quarry”, “The invisible feather perpetually beating its own wings / Floats imperceptibly inside a complete nothingness,” shows what it was that was being parsed by the universe: the paradox of that invisible feather; fleeting moments.

This is getting just a tad long-winded, but seriously, folks, the first poem of this set of four is by far the densest. The second poem, “A Maker of True Form”, according to my notes, in its first two quatrains expands upon, then collapses, all four quatrains of “Quarry”.

In those first two quatrains, there are certain key phrases that I’ve highlighted in my notes: “the trail of trial”, for instance. And the mysterious “res nata”. Also “the gem sheared of its value”. Closing with “the wall of the dig”. At the top of this page of notes: poet/etymology. And a title, crossed out: “Poetymon”.

The reference to “the trail of trial” has more than one reference. We are on a “trail” in a path of life, and it has its trials along the way. (Think Kafka, for an extreme case of that, in The Trial.) There is also the sense of “trial and error” in that we’re just experimenting, feeling our way through whatever this is.

The cryptic “res nata”, according to my notes, means “thing born”, or “small, insignificant thing”. This is what is venturing along that trail of trial, a born entity that, in the face of the universe and whatever is manifesting it, is all but insignificant.

And “The gem sheared of its value” stays in “the wall of the dig”: this perhaps is a reflection that the uncut, unquarried gem—maybe even that res nata, the one that was born—is little if at all noticed by the “dig” that gave birth to it. The “gem” is but a small, insignificant thing.

The last pair of quatrains, according to my notes, is like the emergence of language from “the wall of the dig”. You recall those ancient stories from Biblical days about a certain tower? This “emergence of language” might be related to those stories in some way. “Aahs and oohs…”

And then there’s “A joyous feeding”, which brings in taste and tongue—“a ravening gorge of tongue”, to be sure—and all of it reached by a “walk” (random, chaos, strange-attractor, fractal?) “separated by spaces and times”; encompassing all of history.

As to “ravening gorge”, a gorge is akin to a ravine (“ravine-ing” a homophone for “ravening”), and it’s also archaic for throat (from Old French), and stems from the Latin gurges, “whirlpool”. So this joyous feeding certainly makes for a full belly. And insatiable, at that.

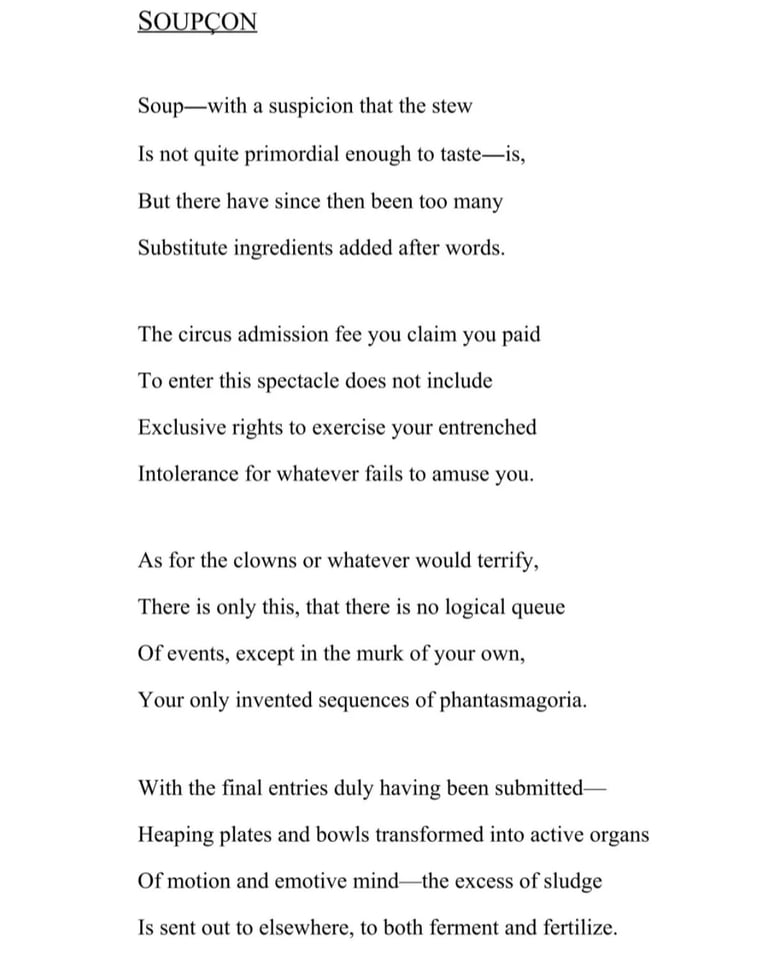

In the first quatrain of “New Ways of Pressing Out” there is finally a hint of movement, by the final line. But first, “New ways”, creative solutions, of “pressing out”, extracting or squeezing the juice out of—out of where? Out of “the bind”, or problematical situation, or “suffering-body”.

These new ways “Enter in at the gateway”—a means of achieving a state or condition, according to my notes—“into the hidden / Initiation”, some kind of secret ceremony, perhaps, “of closed eyes and lips where / No sound tokens presently dance in symbols.”

There’s a lot packed into those three short lines. Sound tokens is my way of saying syllables, whereas symbols are, for instance, letters. Thus, they are both in a sense atomic aspects of words, of language beginning to take form from a more primordial origin, a metaphorical dance.

And they refer back to the last quatrain of “A Maker of True Form”: “Literals, from the first two to two tens with hex, / Are not splittable…” The first two: AB, or alphabet. Two tens with hex: the 26th letter, Z. Are not splittable: as letters (A to Z), atomic units of written speech.

And the quatrain just before that, which references spoken syllables, also atomic: “gatherings of / Verbs and vowels and together-soundings, / Aahs and oohs of clicks filtered down to nouns.” All of this frozen “into gatherings” via “Steadfast zeal”, form contrived “out of no particulars”.

So the dance of language itself is initially frozen, since “No sound tokens presently dance in symbols.” Language is still emerging from the primordial; it’s a preverbal state of consciousness. And closed eyes and lips, no sound tokens? My notes say: “see, speak, hear” (no evil, or anything).

In the second quatrain of “New Ways”, who or what in heck is “The mister”? In this case, it’s not necessarily an honorific, but rather, one who (or something which) mists. The clues are there in the phrase “fogs / All the vapored globe” — suggesting that forms haven’t quite arisen as yet.

But “small confidence trickster” suggests at least an iota of deception. What sort of deception? Because, after all, in some cultures, the trickster is one who possesses a secret knowledge, esoteric in nature, even; and that one may use such knowledge not to deceive but to expose the illusion.

The final two quatrains of this poem are meditations (my notes said “muses”, but mostly:) on creator-destroyer. The third quatrain’s “what is built is toppled” leads so directly to “What is formed is nullified”, which is “disappeared by / The same unknown hand that beckoned it”.

The references to “the unending deep” and “the all-pervading sleep” are simply meditations on self-existence, self-awareness, conscious existence, as beckoned into view by an unknown hand that brought to that existence—that conscious awareness—shape, color, light, and sound.

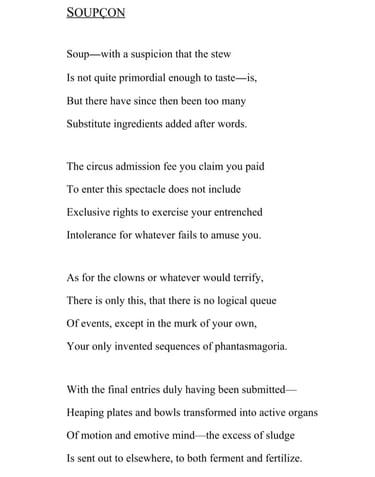

And taste, of course. Soup’s on! My notes for “Soupçon”—a very small quantity of something, and of course also French for “suspicion”—tell me that there is a thin versus thick dichotomy in soup versus stew and that “primordial soup/stew” references the Big Bang/Creation Myth.

And www.bonappetit.com, in “The Etymology of Soup and Stew”, informs me that “soup” is from Germanic roots (for today’s words supper, sup, and sop, as well) which meant “to consume something liquid”, and that a Latin word, suppa, meant “a piece of bread eaten in a broth”.

Later on, the French version came to mean both the broth-soaked bread and the broth itself. When it entered the English lexicon later on—bonappetit.com informs us that a broth without bread became the rage in the 17th century— “soup” more or less replaced “pottage” or “ broth”.

On the other hand, “stew”, when it first came from the Old French estuve, initially referred to a stove, heated room, or cooking cauldron, from Latin extufare (“evaporate”), which was from the Greek typhos (“smoke”). Then it took a wild trip from steam bath to brothel and finally stew.

Perhaps, suspiciously enough, this is part of the reason I’ve highlighted the last two words of the first quatrain, “after words”, the last two lines reading “But there have since then been too many / Substitute ingredients added after words.” Yet: soup is. Even if “not quite primordial enough to taste”.

The middle quatrains address certain existential issues that we all probably deal with from time to time. But this existence is addressed as a “circus”— complete with “admission fee” paid in order to “enter this spectacle”—and features “clowns” or “whatever would terrify”.

This all points to the central dilemma of existence, namely creator-destroyer, alluded to in “New Ways”. But in this poem, it all wraps back to food and more particularly digestion; this universe and this conditional existence is in a sense like a mother that eats its own young.

This final point becomes clearer in the last quatrain, where it is plainly laid out that this is all cycle-return, like QUARRY-ESCAPE-PREY, except in the form of a shape shifter where what once was is recycled and becomes something else. And, like the clowns, it fails to amuse you.

The “active organs / Of motion and emotive mind”—made possible by those “Heaping plates and bowls” that were transformed into them through digestion and assimilation—later become an “excess of sludge” that is “sent out to elsewhere, to both ferment and fertilize.”

Coulrophobia (extreme or irrational fear of clowns), whatever fails to amuse you (and your intolerance thereof), and bacteria all meet in this circus of stew and soup that mystifies, terrifies, and delights us all—in nutritious fermented foods, in the gut, in the soil.

In Praise of the Quotidian, by Robert Fuller

Blue oyster babies: The one cluster seems to want to grow, so I’m continuing to water it and monitor it. If the little ones don’t appear to have stunted growth, and they actually start to mature, I’ll send some photos your way. I just now took a photo, in case they actually do grow this time. What’s my best guess as to why they finally wanted to grow, if they actually do start growing this time? It might have something to do with the recent increase in humidity because of the last few days of rain.

But this cluster also looks more like what blue oyster mushrooms normally look like, which is that they have blue caps (light blue, in this case). And that’s partly a result of my having moved them a bit closer to the kitchen window; although mushrooms can’t really tolerate direct sunlight, their health and the color of their caps are positively influenced by brighter indirect sunlight, or even room lighting.

What I like about little “stories” like this about mushrooms (and the birds and squirrels in the yard) is that there’s something endearing and personal about them—if the person telling the story feels a real connection to the birds or mushrooms or whatever. It feels to me like a bit “Let me tell you a secret,” where you're inviting the reader in, into a world they maybe didn’t know they cared about, but then you tell them in a “just so” way about the intricacies of this micro world-within-a-world, and maybe for at least some of them, it clicks. And they themselves become a bit fascinated by it, too. They start feeling the connection—and then a larger sense of connection with all of this whole damn mystery that’s the world and the incomprehensible universe, yet which is also captured in full in these tiny, insignificant, fragile stories that appear here before our eyes and ears and other senses every day, if only we would notice.

The stories that are normally told are ones of great “importance” and are in general about all the earth-shattering events that we are now so completely surrounded by, with no escape—No Exit, as that famous play by Sartre about the underworld warns us—and yet, I can’t help feeling that there would be no need to tell such stories if only human beings would allow themselves to become maximally sensitive and empathic toward everyone and everything; were that to really happen, there would be no need to tell such stories because they wouldn’t be happening in all their horror and devastation and senselessness. And then people might begin to realize that the real stories, the most important ones, are not about those self-important types with grandiose ambitions and insatiable lusts and desires to in some sense do something important, or at the very least something of such notoriety that they are remembered in the dark annals of human strife and history.

Those are not the stories to tell. We need to go beyond such stories—because finally, such atrocities and self-obsessions and negativities would no longer be happening, and would no longer be tolerated. It’s the simple, modest, homely stories that are the tellable ones, and which might even serve to delight rather than petrify us. In many indigenous cultures and traditions, there were (and still are) many such stories about the lands and the spirits and the living beings and the journies through all of these, where the lands and the spirits—and all else—were simply walking meditations on the spirits and the ancestors and the living land and the mysterious, breathing, conscious, present source of all of it.

This is in part why I sometimes write in direct conversation or communication with friends, partly because I know they’re listening and they care, and partly because these friends and others are a source of inspiration to me. I in turn listen, before and after, and often, it’s by reading what others have written, that the spark of inspiration is lit.

Email Ruminations on Ephemerality

The Allure of Flash Fiction, by Robert Fuller

There is a mystique of sorts to committing yourself to writing a different story at least one a day, for a full year. You don’t know what you’re getting into, at all. You don’t know, on any given day, if you should be committed to some kind of institution. The challenges that arise in this kind of endeavor cannot be foreseen until you actually try the exercise. You will find your ability to write challenged to various extremes, of course, but you will also sigh and say to yourself, on any given day, “Now, what is there to write about?” And you will sigh and sigh and sigh again, and then something clicks, and you say “Aha!”

But the topic of the day is not even half the battle. You still have to write, write something... Anything! And when you settle down, if you are truly ready to take today’s plunge, you find that your mind becomes focused, and then in no time at all, what you were going to write about starts writing itself, at least from your perspective.

So this daily challenge is not pressure, per se, it’s more of an intense motivation that grabs you in every corner of your being and heightens your awareness of the words that you are sculpting for yourself and others to read. And you find a way to breathe, and the words flow, and it’s often in ways you never would have imagined.

It is my direct experience that the place where you choose to write whatever it is you write can profoundly affect what you are writing. Something, anything, can happen right there where you are doing your writing, and there can be a major change in direction because of whatever it was that happened. There can be a pure white dove that heads toward the fountain for a drink of water; but that was the last thing you ever might have expected to see! And then the dove becomes more than just that; and you see that what you were writing was more than just that.

So, day after day of just writing, it takes a toll on you; of that there’s no doubt. At the same time, you continue to hone your wordsmith abilities every single day, and you develop themes over time that return in different ways, and each time you finish a new Flash Fiction, even if you think it’s not all that much in the scheme of things, it becomes another seed for ideas that could feed your other writings; and any of these pieces you’ve done on a daily basis could well be the seeds for even greater and richer writing, going forward. Each of your pieces of Flash Fiction has the potential to grow into something that has as yet never been imagined. And that’s why you keep writing, despite the odds.

June 18, 2024 [18:02-18:35]

The True Nature of Translations, by Robert Fuller

There are some, maybe even many, who say that a translation of an original text is a flawed replica of the original, one that doesn’t capture it sufficiently, that doesn’t do it justice. Over time, I’ve developed a different appreciation of what a translation is and does.

For anyone who has sufficient understanding of the language to which the original is being translated, it may become apparent that the new language is not so much a flawed replica of the original, but that it gives new meaning, new nuances, to what the original text said.

Each language has its quirks, its rules, its way of saying things that can’t be said. And if you get a composite of two, three, or more of these ways of saying things, you most likely get an even more complete picture of what the original text said than that text itself, absent anything else.

There are those of us who luxuriate in these ways of saying things that can’t be said, and we swear by translations that bring things into new lights. Such translations only serve to inform us, the readers of such texts, about what such texts really mean.

Each language has its own quirks. This is a topic for another time. Yet each can inform the other in unique and unimagined ways, and these “flawed” ways of striving to say what cannot be truly said, in any language, should be embraced as the heightening of what the author already tried to say.

June 18, 2024 [19:04-19:24]

Refuge in Creative Pursuits, by Robert Fuller

I can’t speak for anyone else, but in today’s incessant news cycles, often I’m in need of a kind of cocoon, a place to go, where whatever I am, whatever I do, is incubated in such a way that hopefully something positive results from it. I am not one of those whose head has to be buried in the sand, avoiding at all costs noticing what is happening to us on a daily basis within the framework of this fragile human condition, or what is happening to the ecosystem that we, and all living beings, are dependent upon for life and for thriving and for doing better than that, by flourishing, by shining brightly, by making things better.

I am one of many who is daily becoming more elderly and perhaps more frail, to one extent or another, and the barrage of challenging news that hits us on a daily basis nowadays is sometimes very hard to process, or even deal with on any level. So, to whatever extent possible, it is my sincere feeling that we all need a refuge, a space to breathe and be, just be, so that we can replenish what we lose daily with this onslaught of disaster that has become the main item on the menu with each passing news day, or hour, or minute.

My recommendation to anyone in this type of situation is to embrace your inner creative self in whatever way or ways you can, and to spend some amount of quality time, on a daily basis, engaged in those creative pursuits that best allow you to channel your energies in whatever way you can toward a positive outcome, whatever it is you are doing. In my experience, if you have more than one way that you enjoy expressing yourself creatively, you have an important tool in your toolchest, which is that your inspiration can be fed and nurtured in two or more directions, and each spark of inspiration in any of your areas of endeavor can serve to light the kindling of whatever you are doing in your other creative pursuits.

My main cocoon, my main refuge, in the last two hundred days or so, has been the discipline of writing, on a daily basis, at least one Flash Fiction piece, and I have managed to do that through thick and thin. The logistics of making that happen can be—or at least feel—daunting. Where does the next idea come from? That is one of the most pressing issues. Yet the ideas continue to flow, and I continue to write.

Once an idea is in place, then what!? In my case, most typically, I set myself a specific start time, and a specific (yet malleable) end time, and then, once the clock has started, in most cases, I’ve entered that cocoon, that safe place where my focus shifts magically to making the illusion that I am about to make in words take tangible shape, and it’s really just then that the magic itself starts to happen, often beyond any direct control I may have imagined I had over the premise or idea before I actually started writing.

Many writers have mentioned this kind of thing, where what is written is soon beyond their direct control, and the tale told begins to take on a life of its own. My assessment, in the case of the “time trial” writing exercises that I’ve been doing for nearly two hundred days straight, is that each such instance of the story taking on a life of its own is possibly more intense than what is usually described, in that, whatever the story will be, it will last for mere hundreds of words, perhaps a thousand or more in certain cases, and the writing will in most cases take around an hour or so, give or take.

The intensity and focus characteristic of an exercise such as this requires ways for the author to empty the mind of encumbrances, at least every now and then. So I have certain other creative pursuits, and even mindless activities, that I tend to turn toward whenever the mind has become excessively burdened or cluttered with detritus. This is an important part of how it is that I’m able to refresh the creative muse of writing, to whatever degree I do, on a daily basis.

My main go-tos nowadays tend to be free improvisation (on the piano and/or synthesizer) and food prep, including dreaming up new recipes.

Mainly, what you want to do if you pursue the type of writing experiment I’ve been doing for over six months straight on a daily basis is to keep it fresh, and get your inspiration wherever you can. And have fun, lots of fun!

August 23, 2024 [15:55-16:47]

A Year Of Daily Flash Fiction, by Robert Fuller

Being that the year anniversary of my Flash Fiction experiment is a mere two weeks or so away, I thought it might be useful, at least to me, to reflect on what various aspects of this project have taught me. Roughly two weeks shy of the one-year mark, having written over 175,000 words, with at least one Flash Fiction piece every day, I can say with confidence that a project like this is both exhausting and exhilarating. My working title for this experiment, as I should make a point of mentioning, is “Flash Fiction Test Kitchen”, and if and when this experiment is published in one form or another, it will hopefully be clear to any potential readers that there are both merits and downsides to such an experiment.

In a test kitchen, at least as I imagine it, the composer of new taste sensations begins by thinking outside the box, considering ingredient combinations and novel ways of food preparation that perhaps haven’t yet been tried. And some of those approaches will prove to be excellent, while others will be maybe so-so, and yet others may end up as complete failures. The same is true, by the way, when one does free improvisation, in the field of music, or perhaps theatre, or perhaps dance. But what is gleaned from any such experiments is that even the complete failures might end up as the seed for something else that might never have been imagined if it were not for that experiment.

In the case of this nearly yearlong project of mine, I have experimented with numerous different writing styles, and, this close to the project’s conclusion, one of my main takeaways has been that much of my writing throughout this year has been essentially a kind of prose poetry. And, in many cases, there might be a kind of disconnect between the title and the main body of the text, which also tends to make such a text essentially a riddle of sorts.

Another thing that has happened during the past year or so is that from one Flash Fiction piece to the next, over time, there are themes that begin to emerge, with characters who recur at odd times without much explanation, and so there is a kind of continuity from one end of the project to the other. Much of this has to do with the fact that much of what I do I consider in a very real sense a form of music composition, in which there are motifs that not only recur but are embellished and made into variations and developed much as might have happened in a Beethoven sonata form, or a Bach fugue—or a free improvisation that seems to have no rules yet has its own interior logic and hidden patterns.

It is difficult for me to see the bigger picture, the perspective from above, so to speak, with regard to this project, being that I have been metaphorically in the daily trenches and have not yet reviewed the entire project as it now stands in a single reading. But what I can impart to you without a doubt is that the daily practice of having to write something, if taken in the right spirit, has the potential to focus the mind in ways one might not imagine possible. And this is especially true in my own experience because of the way I have normally chosen a particular starting time for the writing to begin (and usually with a set ending time) and so when the starter gun goes off my mind usually tends to be laser-focused on the writing experiment at hand.

The musical aspect of how I tend to work has in large part to do with how the words sound when juxtaposed but also how they tend to resonate with each other in those juxtapositions especially in English in which there are so many ways of creating multiple meanings by means of synonyms and ambiguities and crystal clear clarifications and so many other ways of creating a nice kind of chaos that hopefully invites one to ruminate on deeper meanings and all kinds of paradoxes without too many rules that might get in the way.

There is a chance I might have more to say about this project but let me leave you with this for now: Much of what I have written during the past year is prose poetry in which the elements have been juxtaposed to create various vignettes or paradoxes or even what you might consider a kind of parable. And much of my most recent writing (as of this date, January 29, 2025) has been intended as a sharp “political” critique of the extremely sad state of affairs that is currently the case in the United States.

For anyone who might be reading this and who might be an aspiring writer, if you happen to have writer’s block, I would strongly recommend choosing an existing text of your choice, one that you find inspiring, and using the words in that text as your selected vocabulary, which should focus your mind and your energies on finding new connections between words and phrases that no one has yet imagined. For an exercise of this type, you should limit yourself in the text you are writing to only those words that appear in the original text, and for any such word, you should limit the number of times you use the word in your text to the maximum number of times it appears in the original. And, as you can probably guess, you need not use every word from the original in the text you are writing. But the main point is for you to make poetic connections between words and phrases from the original text, while at the same time coming up with a completely new composition that is not merely some kind of paraphrase of the original.

I hope you have found this interesting and perhaps even useful.

January 29, 2025 [16:35-17:36]

A Few Reflections On Keyboard Improvisation, by Robert Fuller

There is a strong connection between three of the main aspects of music, namely, performance, improvisation, and composition—not to give short shrift to other disciplines within the sphere of music such as theory, analysis, history, and others. But the first three mentioned, as was taught to me by my PhD advisors at University of Iowa, where I majored in Music Composition, with a special emphasis on electronic and computer music, well, they are kindred spirits within a continuum. I often like to say that when I improvise, I forget just about everything I ever knew about piano performance, music theory, and the like—but that’s not necessarily 100% true, and it’s probably just more on the order of a “wish list” item.

You see, you can’t completely forget any of what you’ve learned, in this or in any other discipline, if you wish to freely experiment, relatively speaking free of the usual shackles, so to speak, of whatever it is you’ve been taught or that you’ve learned through experience. All of what you’ve experienced or learned, you see, serves to feed what you wish to do when you freely improvise. And in fact, that observation, that of somehow being fed, is one of the keys to what you are really doing when you improvise. It’s known as a feedback loop.

A feedback loop, simply stated, happens when a system of some sort—you, for example, as the improvisor—takes in signals or data or sounds and the like, and then responds in some meaningful way to that input in such a way that the output that happens afterward is affected, altered, transformed, in a meaningful way. So if you with your eyes closed begin to play notes, rhythms, harmonies, what you play next, if you listen and respond carefully enough, will be in some sense meaningfully transformed by what you have just heard.

Music performance—and in this specific case, I’m referring to the performance of a musical score written in conventional music notation within the European musical tradition—at its best embodies that same kind of feedback loop, in which the performer listens and responds to what they have played, and then that affects what happens next. And at best, you get a sensitive rendition of what the composer has so carefully and meticulously written down.

Music composition, then, within that same tradition, is the flip side of the same coin, wherein the composer is writing careful and meticulous instructions as to what the performer or performers are to perform, based on what the score stipulates within the realm of standard music notation. And so, as might be obvious, the musical score is a blueprint for a very specific design that the performer is to adhere to, which can and should be embellished in various meaningful ways by the performer or performers and how they respond to whatever happens in real time during the scope of the performance. Yet it is also true that music composition is improvisation.

Think of the artist and the blank canvas. In order for a painting to emerge from the otherwise blank canvas, the artist has to listen or look or feel, and then respond in a meaningful way to whatever impulses might come up. The composer is in a similar situation, wherein there is no set way to start putting notes on the staves on that blank music paper. Inspiration ultimately comes from somewhere, but the writing of that music, much as with the writing of a novel, or the creation of a new culinary sensation, goes in fits and starts, and in most cases the ultimate outcome is not known in advance.

So then, any compositional act is really just a performance, an improvisation, but in slow motion—not in real time. And this observation brings us to the central point, in music, in this case, that performance, composition, and improvisation are parts of a trifecta of sorts, three parts of a three-ring circus or circle, that are, curiously, directly related. They all involve feedback loops in a very real sense. Two of them happen in real time, and the other happens in slow motion mainly within the mind and heart of the composer, who is in some sense striving to create an architectural blueprint on a blank page.

And then there is the very real sense in which improvisation is in many cases an act of composition, because in most cases, it is impossible to jettison what you have learned through your various influences, which means that you are drawing upon them and in some sense repeating or otherwise reinforcing what you have learned or experienced. And so improvisation is in a very real sense “composing” music in real time.

The two main keyboards I have been using for improvisation most recently are the piano and the synthesizer—specifically, the Nord Lead 2 “virtual analog” synthesizer. I have used them both singly and in combination, and each keyboard has different attributes and challenges; and the use of both at once brings in a whole new world of possibilities and challenges.

When I improvise on the piano alone, because of the relatively homogeneous nature of the piano “sound”, I often tend to gravitate toward softer, somewhat bell-like sounds, and rather more supple, fluid rhythms. Over the years, it has been my observation that, if played softly and subtly, note combinations that might otherwise be perceived as jarring dissonances, when played at a higher volume, can be quite soothing and mysterious. And the more supple, fluid approach to rhythm can have a similar effect, in my experience.

In the case of many or most of the improvisations I do, in the moment when it happens, it is often most directly a feeling matter. The act of listening and responding is part and parcel of the feeling aspect of what I do, but what I’m referring to as feeling is also the literal touch of fingers on the keys, and the bodily movements that occur within this feedback response.

Now, the synthesizer aspect of what I do, with the Nord Lead 2, well, that’s a whole other ball of wax. You see, the main starting point, when you begin to improvise with the Nord Lead 2 and other similar synthesizers, is what you call the “patch”. I’m fairly certain that this name stems from the use of multiple patch cords on, for example, the original Moog synthesizer. In the case of the Nord Lead 2 “virtual analog” synthesizer, there are no actual patch cords, but the patch still refers to much the same thing. It’s a particular configuration of the synthesizer that, initially, results in a particular “sound”—which includes more complex combinations of various sounds, depending on how the patch has been set up.

The patch, then, on the Nord Lead 2, is the whole key to what you will get out of those keys when you play them. And then there are all sorts of knobs and toggle buttons and other controls that you can change during your improv that can be used whenever you wish. So it is very easy to change not only what keys you play and when, but also the very sound colors, the timbres, and even the rhythms and many other aspects of your real-time performance—and in many cases, it is possible that you will find yourself in a completely different soundscape than where you just were, merely at the touch of a button!

It is possible to learn how the modules of a synthesizer such as the Nord Lead 2 interact and what they do, but in my assessment it is virtually impossible to figure out how, in any given patch or configuration of that synthesizer, any given button or knob or other control will affect the next sound you get out of your keyboard.

So this aspect of the use of this type of synthesizer means that when you are performing something on it you will have to listen and respond closely and you will always have to be in some kind of intuitive mode. For me, the fact of the relative unpredictability of performing on this and similar keyboards is a great part of the charm and challenge of working with it. And the rewards can be immense; you can discover new soundscapes you never knew existed; you can improvise something that warms your heart like nothing else; you can find ways to connect to your fellow human beings through unique sounds and soundscapes that are not easily reproducible and you can hopefully warm some of their hearts as well. But working with synthesizers like this can be difficult, as well. Sometimes it can be difficult to find a patch that you can work with, and sometimes you might find it difficult to find anything at all.

When working with both the piano and the synth within the same improv, it often comes down to what the hybrid sound of the two keyboards is. And you have to adjust expectations for whatever either hand is doing with whichever keyboard, and you have to carefully listen to and respond to the sounds that come out. Yet these sounds can be some of the most intricate you might make. The two keyboards might be detuned to some extent, for example, in which case you might be creating a performance that is to one extent or another microtonal. The synth might be geared toward a regular rhythm because of its configuration, and that might end up driving what you do with the piano. And then you might end up in various types of “twilight” zones you never would have anticipated.

A final reflection, for now, on improvisation in general, is that when you add others to what you are doing, so that it’s no longer just you, you will find that what you do and how you do things is altered, since now it’s not just you in your own feedback loop, but it’s also you responding to one or more others and what they are doing, and that’s another whole can of worms. And that is both the fun and the peril of it.

February 10, 2025 [17:00-18:52]